North Philly library branches are embracing a new, modern role: filling the gap left by rec centers.

As a 21-year-old mother of three, Mieka Moody arrived at Central Library to take a library assistant exam practically by chance.

“When I was a child, I did not say I wanted to be a librarian,” Moody says. “Actually, I did not even spend a lot of time in libraries.”

Among the crowd of 100 or so test-takers was her mother, who had been studying for weeks. The results came in and her mother didn’t make the cut. Moody did.

Now, Moody is the branch manager and sole librarian of the Lillian Marrero library, located at the corner of 6th Street and Lehigh Avenue. The South Philly native spends most of her days managing the kids that come to her library, from supervising homework to making slime.

In the city that founded the free library system (thanks Ben!), the 54 branches of Philadelphia’s public libraries are drifting much further from a book-centered model than our founding father ever could have imagined. As a source of free internet and air-conditioning, libraries have long been a space for community members to hang out in their spare time. But as the City of Philadelphia fights to keep community centers alive, libraries have slowly taken their place, particularly in low-income areas such as North Philadelphia.

“I look at libraries now and, okay, books are important, books will always be important,” Moody says. “But right now I think libraries are changing into, like, this social hub where you can interact with people, get other ideas from people and just become open.”

This means Philadelphia librarians are taking on extra work to meet the needs of the community. When Moody’s Lillian Marrero branch received extra funds last year, she held a mindfulness group at her branch, complete with a yoga class set up on the ground floor. The library also holds weekly produce giveaways in the parking lot. One of her assistants created a crocheting club. And she’s not alone. Children of the McPherson Square branch participate in a Make Jawn program for STEM-related activities and are provided a daily hot lunch. Lovett Library’s Marsha Stender created a Dungeons and Dragons club at the request of a patron.

“We do what we can so they can do something constructive while they’re here,” Stender says. “And we tolerate a certain amount of noise; libraries are not quiet places once the kids arrive, that’s for sure.”

******

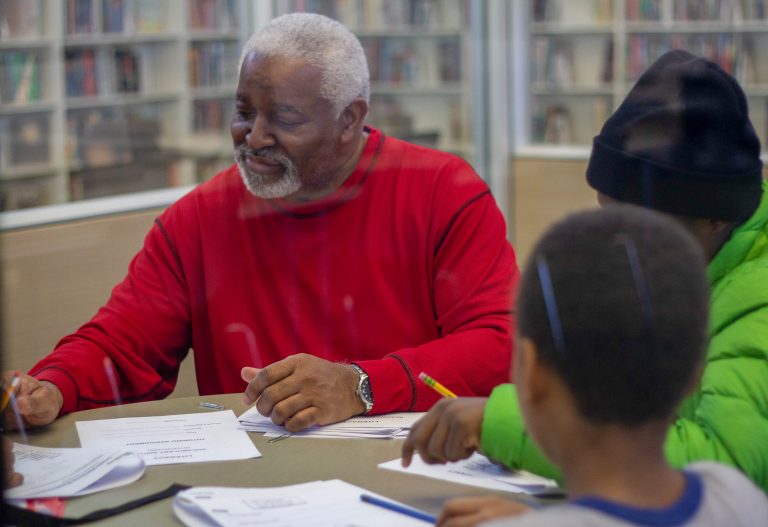

Everett is a regular patron of the McPherson Square branch in Kensington. He can be found sitting right next to children’s librarian Judi Moore’s desk, spending most of his time playing on a tablet. When asked why he chooses to come to the library every day, he shrugs and answers, “I’m bored at home.”

The McPherson branch, located in the center of the city’s opioid crisis, made headlines earlier this year when it Narcan-trained its staff after several overdoses occurred on the premises. To help protect them from exposure to drug use, Moore said her branch and the park across the street have been declared a safe haven for children. “This is where the kids need to be,” she says. “There’s a playground here that the Flyers donated. It’s a natural place to say, ‘This is for the kids.’”

Adding more programs to each branch means more costs and more work for each librarian, with no extra incentives. The funds for each branch come in part from city and state funding, and the rest from private funding and donations. Each branch has the exact same pay-cap, meaning librarians at two different branches can be making the same amount despite one having more patrons, less staff and therefore more responsibilities.

Moody said that since her library is located in one of the poorest zip codes in the city, her Friends group (a private organization that provides supplementary funds for each branch) is still getting off the ground. With few resources in the area, there is little money to be given to the group itself.