Monica pops her head into her coordinator’s office at 6:50 p.m. on a Sunday. She’s sporting purple from the hem of her scrubs to her head wrap, barring the blue disposable mask covering most of her face.

“You know anyone selling dogs?” she asks. “I’m looking for something small and fluffy. I wanna be able to carry it like this.” She cups her hand tightly at her side and chuckles. Rachel is the coordinator of the residency program. Monica is one of her residents. The two talk puppies for five minutes, then Rachel pauses to ask how her day has been.

“Not bad,” Monica shrugs. “Three people died on ICU, but that’s pretty much it.”

They then resume their conversation about puppies.

Monica is a second-year resident at the hospital. Since 7 a.m., she’s been working under Naomi, a third-year resident. Today is their seventh day in a row working the 12-hour shift, during which they admit new patients, tend to current ones, and respond to any emergencies that may arise. This can range from administering Tylenol to performing a C-section. On weekends, the residents on duty are the only two doctors in the 146-bed hospital.

There are 18 residents in the residency program at any given time. First-years have just finished medical school and third-years graduate from the program every June. After their residency, they’re fully certified doctors.

Shift change happens at 7 a.m. and 7 p.m. every day. The two residents on duty switch to another two for the next 12 hours. In tonight’s case, Naomi becomes Sydney and Monica becomes Danielle. The new team will work until 7 a.m. and will once again be relieved by Naomi and Monica.

The family medicine department is a narrow hallway with several rooms. Some of them are offices like Rachel’s, where administrators keep the show running smoothly. There is a conference room where, pre-COVID, dozens gathered for meetings. Two on-call rooms provide night-shift residents with a desk, a computer, and a twin-sized cot to rest in between duties.

The hall leads to a snack-stocked kitchen and a small room with a couch, two desks, and two computers. This is where the shift change takes place.

Monica has passed her baton to Danielle and left for the evening. Though Sydney has arrived to relieve her equivalent, Naomi remains in the back room, her head resting in her left hand, her right hand vigorously scrolling the wheel of the computer mouse. It’s already 8 p.m.

Naomi makes a call to two doctors not currently on the premises to update them on several patients. This is an integral part of the shift-change process. A bulletin board that reads, “COVID Information and Updates” hangs on the wall above her. A bubbly font on pieces of printer paper, it looks like something from a middle school hallway. Instead of book reports, it displays crucial information about a deadly virus.

Naomi stays on the phone for over a half hour, being pulled away multiple times and pausing to answer calls on another phone. She works through a list of twelve patients, briefing her colleagues on the medical history and diagnosis of each:

“His abdomen was very large. He was tapped and they got 8 liters off of him.”

“She’ll likely go the Hospice route since she can no longer swallow her medications.”

“She had COVID in March and still can’t feel her legs. We think it’s polyneuropathy.”

On the other end of the call, Naomi’s rundowns are met with “mhm”s and the occasional clarifying question.

Meanwhile, Sydney and Danielle sit at the other desk, assessing a list of emergency department patients to prepare for their shift. They get two admissions– one in oncology and the other in cardiology.

“I don’t know what the ED thinks they’re going to do for her,” Sydney says about a patient who’s clearly been admitted before.

“What is she in for?” Danielle asks.

“Headaches.”

“Headaches?!”

“Like, she has a brain infection,” Sydney says like a sassy pre-teen who’s been through med school. “She’s gonna have headaches.”

Out of 126 current patients in the hospital, 19 have the coronavirus. But Sydney and Danielle feel that the pandemic doesn’t change much for them. They work tirelessly regardless– now they just have to wear a mask and try to distance while doing so. By now, it feels normal.

“Not much is different,” Sydney says. “The only thing is that we have to treat everyone as if they’re positive.”

Her and Danielle mention how patient flow, or the strategic placing of patients in rooms, can be challenging depending on how many COVID patients there are. They also talk about the use of negative pressure rooms, which act like vacuums to keep infectious illnesses contained when the doors open and close. Aside from some logistical considerations, the residents’ roles remain unchanged.

Naomi finally finishes her phone call, prints a list of patients, and hands it off to Sydney. She ends her day an hour and a half later than expected, which is evidently not unprecedented. For the next ten and a half hours, Naomi is free to sleep, eat, and think about puppies. But at 7 a.m., she’ll return to the hospital, slap on her PPE, and become superhuman once again.

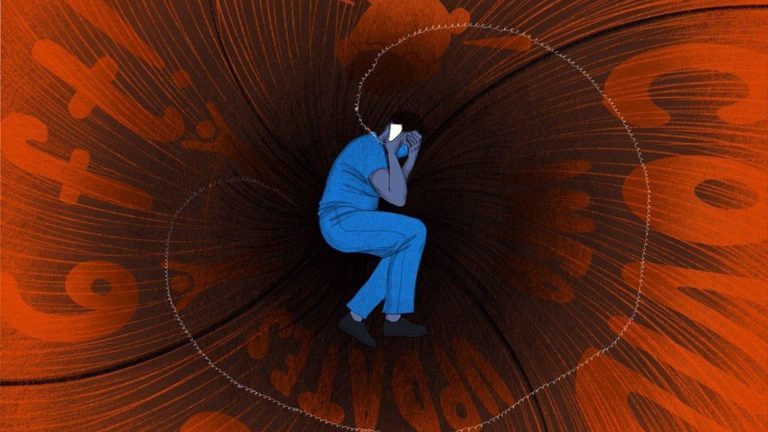

Illustration by Olivia Musselman