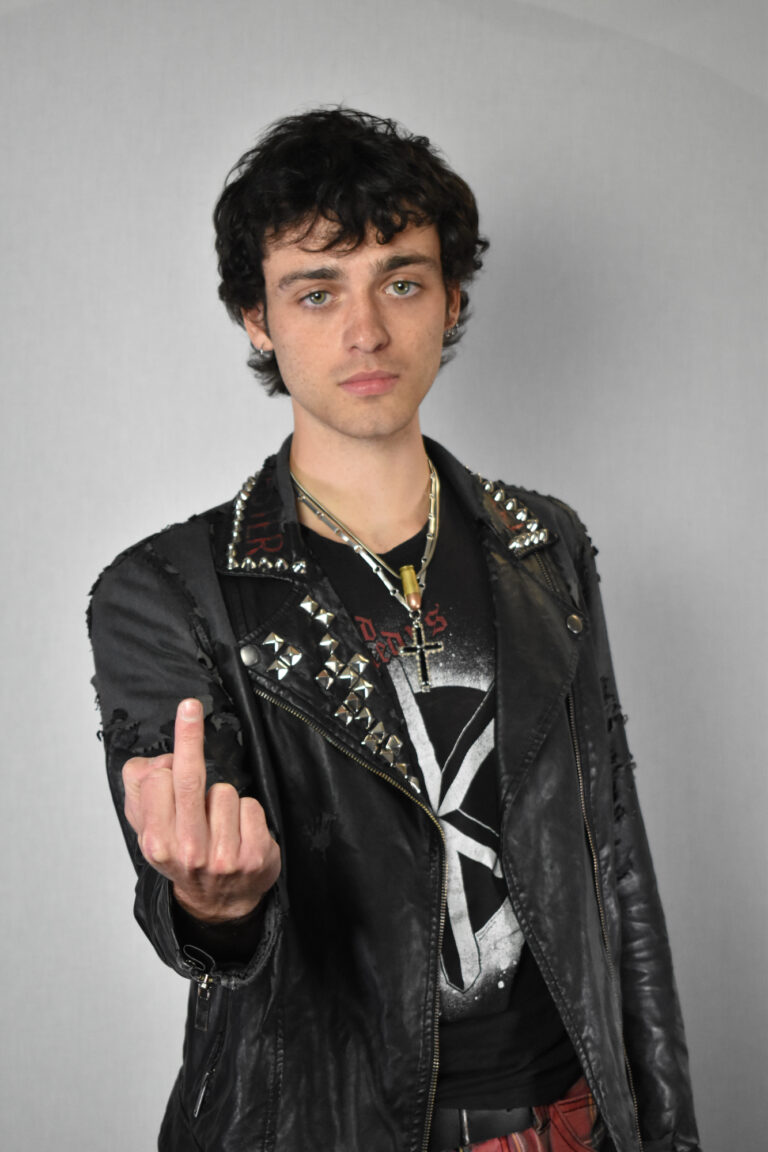

Once a snarling rebellion against the mainstream media, punk was never just about the music—it was an identity, a lifestyle, a loud middle finger to the status quo.

But decades after its explosive birth, the meaning of punk or alternative has changed. From safety pins and DIY zines to TikToks and curated playlists, the culture itself has evolved and redefined itself.

While it still gives space for outsiders to connect over shared values and struggles, some wonder if punk is the last remaining subculture in the digital age.

Punk’s cultural expression has undergone a landscape of transformations. It evolved in the 1970s with a new wave of fashion emerging out of London as an anarchic, a term coined by Vivian Westwood, as well as an aggressive movement. Thousands of people defined themselves with an anti-fashion “urban style” street culture.

During this time, major bands like the Sex Pistols and The Ramones had core values of being anti-establishment, a DIY ethic, and being inclusive for any of the “misfits” that had been marginalized. Punk began as a subculture that fought to be normalized among the normal.

At its heart, punk is about being angry. Angry at the political state of the world, angry at systematic practices, just angry at a lot of things. Their style is loud with aggressive tones and the usage of fashion as a protest.

The culture gave a powerful voice to working-class communities and amplified the experiences of marginalized groups, including queer individuals and people of color. As anarchists and anti-capitalists, the shared values of those affected by “the man” wanted things like racial justice. Even before the ‘70s, punk had always existed; many wrestled with these ideas in the ‘30s, ‘50s and ‘60s. Punk ideas were always there, but it was not during a time of revolutionizing standards.

Punk being one of the last subcultures means it had to go through many births and deaths since the ‘70s to be what it is today. The rise of the Skin Head Movement or even the wearing of Dr. Martens are proof of the popularization and many ways the punk aesthetic has been adopted.

In the new digital age, the rise of the term “alternative” has influenced the way people perceive the term punk. Dressing “alternative” in the 21st century has become more of an aesthetic choice rather than an ideology

Temple University Adjunct Professor George Alley teaches Search and Destroy: Punk’s DIY Rebellion, a course that explores the wide-reaching impact of punk music, fashion, dance and DIY culture that emerged in the late 1970s and how it has continued to influence later decades.

“A way for culture to kind of control subculture is to integrate it back into fashion,” he said in a brief interview. “There is a difference between style and fashion. You might create signs and symbols that align you to somebody, and I can tell that somebody is ‘cool’ because they have the same symbol.”

He continued by discussing how at times these symbols, such as having piercings or tattoos, can cast you out of society. But what is consistently happening is that people have been making certain symbols less threatening, and these modifications have turned aspects of a non-conforming culture into modern society, which is mainstream culture’s way of controlling things.

Punk culture is ever adapting and changing with the times. Punk dies just so it can be born again with the new generation in subcultures.

Once punk took a downward spiral in the early 2000s, it became marketed as nostalgic in scenes like London and New York. Nostalgia is partially what keeps the culture alive and allows new punk-heads to add touches of their style. There are so many new sub-genres and bands with new sounds that are still punk, even if it is not in the traditional sense. It is evolving and is as much of a mindset and attitude as it is a genre.

“There were people you could talk to in 1977 or 1978 who would say that punk is over, but this idea is romanticized,” Alley says. “But I think what happens is that it just shifts.”

The romanticized idea comes from those who were a part of the punk scene when it was more welcoming to people of color and the queer youth community. As it became more commercial, these individuals were no longer accepted and adapted by forming their own wave. Subcultures like goth, hyperpop and the new wave are places where punk continues. It may not hold its original meaning, but it continues in new ideas.

Social media platforms like TikTok and Instagram have further reshaped the punk landscape and given rise to digital expressions of punk that often contrast with the raw, in-person energy of traditional punk scenes. Today, punk is frequently grouped under a broader “alternative” umbrella, reflecting how its definition and cultural relevance have expanded and evolved with time.

The chaotic, underground spirit that fueled early punk scenes has, in many ways, been replaced by more polished and performative versions. However, this shift has also brought important gains—greater inclusivity, accessibility and diversity have opened the doors for more voices and identities to participate in punk culture, making it more powerful than it has ever been.

While the aesthetic and delivery may have changed, the rebellious, DIY ethos at the heart of punk still pulses beneath the surface, reimagined for a new generation.

“I think that what evolves culture is taking ideas from the past, and taking different ideas, and putting them together, and have a new juxtaposition of ideas,” Alley adds. “That is when you get something new. New ideas [within the culture] can still happen today.”

The consistent and constant adaptation of this culture is what makes punk, punk.